The Next Level – The Oklahoma Symphony Orchestra

In 1937 an orchestra was created in Oklahoma City as a Federal Music Project (FMP) through the Federal One program of the Works Progress Administration (WPA), and had a solid base of community support from Holmberg’s Oklahoma City Symphony. From the mid-1930s to the early 1940s, the FMP funded programs across the country designed to put musicians to work in all aspects of the field. The $25 million Federal One program also had a stated goal to create a unified American culture as well as generating support for the government’s programs to help citizens during the Great Depression. The offer of federal support came first to Tulsa but the idea did not take hold until culture boosters in Oklahoma City became interested in the idea of rebuilding a city orchestra. The orchestra was licensed in 1937 as an ensemble to serve the entire state but with administration and operations centered in Oklahoma City.

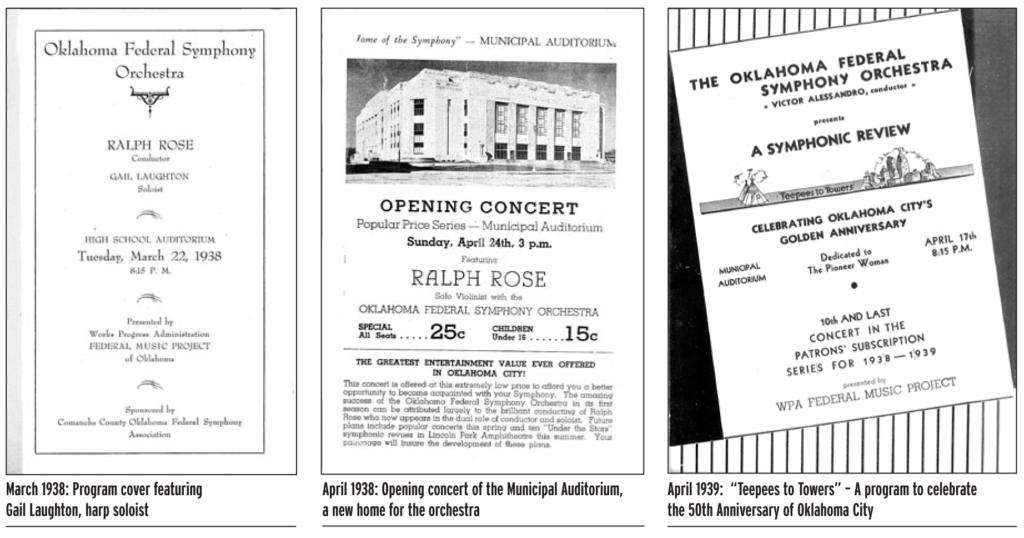

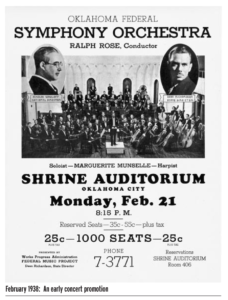

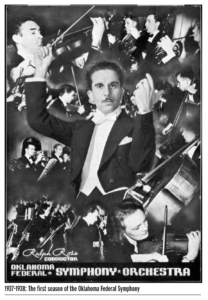

Ralph Rose, the first conductor of Oklahoma’s new “Oklahoma Federal Symphony Orchestra,” deserves credit for putting the orchestra on stage in the face of great odds. Despite being just 27 years old himself, he recruited a group of very young musicians to perform in the orchestra; most were just out of high school. Ninety percent of the players were “certified” for WPA funding because they were out of work. The non-certified musicians were the older players, who generally had more experience. The orchestra presented public rehearsals and open concerts in various schools and at a lodge room at the Shrine Temple. But finally the first public concert, with a VIP ticket costing a whopping 55 cents, was presented to some 3000 people on January 3, 1938, with the orchestra playing the Symphony No. 6 of Peter Tchaikovsky. Guy Maier was featured as soloist in a performance of the Piano Concerto No. 1 by Franz Liszt. Maier, in addition to his position on the faculty of the Juilliard School and his touring career, was affiliated with the WPA as a regional director in New York.

Ralph Rose, the first conductor of Oklahoma’s new “Oklahoma Federal Symphony Orchestra,” deserves credit for putting the orchestra on stage in the face of great odds. Despite being just 27 years old himself, he recruited a group of very young musicians to perform in the orchestra; most were just out of high school. Ninety percent of the players were “certified” for WPA funding because they were out of work. The non-certified musicians were the older players, who generally had more experience. The orchestra presented public rehearsals and open concerts in various schools and at a lodge room at the Shrine Temple. But finally the first public concert, with a VIP ticket costing a whopping 55 cents, was presented to some 3000 people on January 3, 1938, with the orchestra playing the Symphony No. 6 of Peter Tchaikovsky. Guy Maier was featured as soloist in a performance of the Piano Concerto No. 1 by Franz Liszt. Maier, in addition to his position on the faculty of the Juilliard School and his touring career, was affiliated with the WPA as a regional director in New York.

It’s A Raid! Orchestras Compete.

At one point, both Tulsa and Oklahoma City had created private foundations to support a WPA Federal Symphony. As part of the agreement with the FMP, a portion of the operating funds for the orchestra had to come from private support. Civic leaders in Tulsa were opposed to the idea of receiving federal support and were determined not only to fully fund their own orchestra but also have the “best” ensemble in the state. With an offer of an additional $25 per month salary, they lured away 15 musicians from the Oklahoma City project. Unfortunately not only were they unable to sustain the level of donated support necessary to manage an independent orchestra, but they were unable to garner the means to continue as a WPA Federal Symphony. The Tulsa Philharmonic was successfully founded in 1948 and became a thriving regional orchestra for many years.

Throughout that first season, the Oklahoma Federal Symphony Orchestra played more than 50 concerts for children and in many more appearances across the state reaching over 120,000 people. The musicians were paid $75 per month and the organization was managed by a federally appointed director, Dean Richardson. The OKC performances were moved to the newly completed Municipal Auditorium in February 1938 and a concert later that spring featured guest conductor 21-year-old Victor Alessandro, Jr., who would become music director the following year. A youthful Mickey Rooney even took the baton for a rehearsal of the Prelude of Act 3 from Wagner’s Lohengrin that season. Ralph Rose continued to conduct through the summer when a series of “Starlight Concerts” were presented at Taft Stadium (on May at N.W. 23rd Street) drawing crowds of nearly 6,000 music lovers.

Throughout that first season, the Oklahoma Federal Symphony Orchestra played more than 50 concerts for children and in many more appearances across the state reaching over 120,000 people. The musicians were paid $75 per month and the organization was managed by a federally appointed director, Dean Richardson. The OKC performances were moved to the newly completed Municipal Auditorium in February 1938 and a concert later that spring featured guest conductor 21-year-old Victor Alessandro, Jr., who would become music director the following year. A youthful Mickey Rooney even took the baton for a rehearsal of the Prelude of Act 3 from Wagner’s Lohengrin that season. Ralph Rose continued to conduct through the summer when a series of “Starlight Concerts” were presented at Taft Stadium (on May at N.W. 23rd Street) drawing crowds of nearly 6,000 music lovers.

Richardson was responsible for all the FMP activities throughout the state and reported to supervisors at both the regional and federal level. His focus on the new orchestra led him to neglect his other duties and there were complaints about his work. Nikolas Sokoloff, director of the FMP and former conductor of the Cleveland Orchestra, visited Oklahoma City in May 1938 and was “agreeably surprised” by the performance of the orchestra.

The national director gave a brief talk at the concert. He urged the public and the musicians to understand that the Federal Music Project was not a relief program but a works program. The aim of the program, he said, was to provide a permanent intelligent effort toward improvement and progress in musical activities.

– quoted from the Daily Oklahoman, May 3, 1938

Sokoloff’s position was not held universally, even within the administration of the WPA and Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal programs. The New Deal programs created controversy from the start and role of the government was perhaps even more hotly debated then than now. Richardson worked to preserve the financial status and operations of the orchestra while caught in the squeeze between the private and public funders. Meanwhile, the new conductor, Victor Alessandro, worked to build the quality of the ensemble while his forces were routinely lured away by orchestras and bands across the country. The exceptional quality of the musicians coming from the Southwest region was suddenly recognized as the Oklahoma Federal Symphony was acknowledged by some to be the best symphony between Chicago and Los Angeles.

A Good Start

Fifteen year old harpist Gail Laughton (1921-1985) barely made the cut to become a member of the new orchestra in 1937. He was plenty talented but just met the minimum age to be hired into the federal program. Gail made the front page of the Daily Oklahoman at age 4 when he played violin for industrialist Henry Ford. However, his future was made when he moved to California. Gail Laughton had a tremendous career as a jazz harpist, as a studio musician, and provided harp music for many Warner Brothers films and Loony Tunes scores. His hands are featured playing the harp in The Bishop’s Wife, with Cary Grant.

Gail worked closely with Harpo Marx on some of his filmed harp solos and played for the West Coast’s Air Force’s Radio Production Unit. Gail’s beautiful classic recording Harps of the Ancient Temples was excerpted in the Ridley Scott film Bladerunner.

Federal funding for all the Federal Music Projects ended in 1943 and the Oklahoma Symphony Society was faced with the loss of 75% of the orchestra’s budget. Because they had been charged with only supplying only 25% of the necessary funds as the sponsoring organization, they had found a comfortable level of support within the community. The group struggled for several years but accumulated a significant deficit and then voted to liquidate the orchestra in July 1945. The action shocked the community and sufficient support was raised to continue operations. However, there were structural changes that were necessary to create the independent organization. The board of directors was reorganized and included 36 members and the name was changed to The Oklahoma State Symphony Orchestra.

The First Anniversary

The first anniversary concert of the Federal Symphony was held on Thursday, January 5, 1939, and was billed as a “Fun Night: Celebrating the First Birthday of the Oklahoma Federal Symphony Orchestra.” Patrons were promised a program of nonsense and hilarity, laughs and surprises and warned that “Anything (or almost anything,) goes…”

A promotional announcement listed selections including “Pops Goes the Weasel,” “Toy Symphony,” “The Chicken and the Worm,” “Fleas,” “Hippo Dance,” and other whimsical pieces. Patrons were warned that this program included “some of the things we may do if we feel like it –“